A shocking number of birds are in trouble

We know better than ever how to help endangered birds, with notable conservation successes.

Just about anywhere you look, there are birds. Penguins live in Antarctica, ptarmigan in the Arctic Circle. Rüppell’s vultures soar higher than Mt. Everest. Emperor penguins dive deeper than 1,800 feet. There are birds on mountains, birds in cities, birds in deserts, birds in oceans, birds on farm fields, and birds in parking lots.

Given their ubiquity—and the enjoyment many people get from seeing and cataloging them—birds offer something that sets them apart from other creatures: an abundance of data. Birds are active year-round, they come in many shapes and colors, and they are relatively simple to identify and appealing to observe. Every year around the world, amateur birdwatchers record millions of sightings in databases that are available for analysis.

All that monitoring has revealed some sobering trends. Over the last 50 years, North America has lost a third of its birds, studies suggest, and most bird species are in decline. Because birds are indicators of environmental integrity and of how other, less scrutinized species are doing, data like these should be a call to action, says Peter Marra, a conservation biologist and dean of Georgetown University’s Earth Commons Institute. “If our birds are disappearing, then we’re cutting the legs off beneath us,” he says. “We’re destroying the environment that we depend on.”

It’s not all bad news for birds: Some species are increasing in number, data show, and dozens have been saved from extinction. Understanding both the steep declines and the success stories, experts say, could help to inform efforts to protect birds as well as other species.

The bad news

On his daily walks at dawn along a trail that snakes by several reservoirs near his home in central England, Alexander Lees typically sees a variety of common waterfowl: Canada geese, mallards, an occasional goosander, a type of diving duck. Every once in a while, he spots something rare: a northern gannet, a kittiwake, or a black tern. Lees, a conservation biologist at Manchester Metropolitan University in the United Kingdom, records each sighting in ebird an online checklist and growing, global bird database.

Lees studies birds for a living, but the vast majority of those who track the world’s 11,000 or so bird species, either on their own or as part of organized events, do not. Hundreds of thousands of them participate each year in the great backyard bird count launched by the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and the National Audubon Society in 1998: For four days each February, people tally their sightings and the data are entered into eBird or a related identification app for beginners called Merlin.

The north American breeding bird survey, organized by the US Geological Survey and Environment Canada, has enlisted thousands of participants to observe birds along roadsides each June since 1966. Audubon’s Christmas bird count which began in 1900, encourages people to join a one-day bird tally scheduled in a three-week window during the holiday season. There are shorebird censuses and waterfowl surveys, all powered by citizen scientists.

This wealth of longitudinal recordings started to turn up signs of distress as far back as 1989, Marra says, when researchers analyzed data from the North American Breeding Bird Survey and concluded that declines were occurring among most of the species that breed in forests of the eastern United States and Canada, then migrate to the tropics.

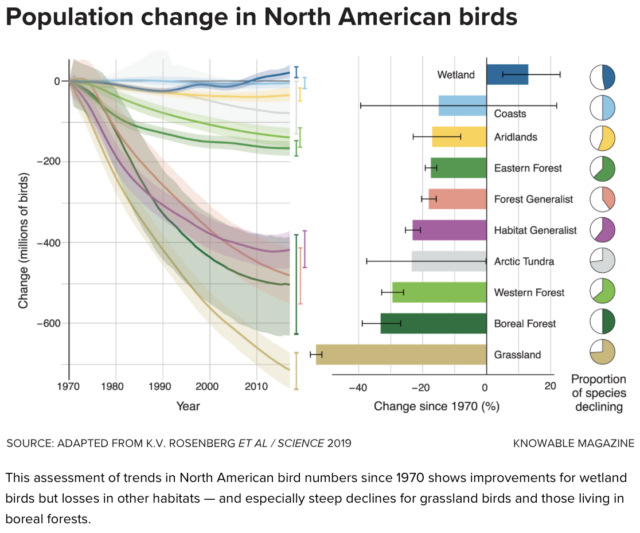

Thirty years later, Marra and colleagues reassessed the situation using multiple bird-monitoring datasets from North America along with data on nocturnal bird migrations from weather radars. They found stunning losses . Since 1970, the team reported in Science in 2019, the number of birds in North America has declined by nearly 3 billion: a 29 percent loss of abundance. The paper used several methods for estimating changes in population sizes, Marra says, and “they all told us the same thing, which was that we’re watching the process of extinction happen.”

More than half of the 529 bird species assessed by the study have declined, the team reported, with the steepest drops in grassland birds, which have suffered from habitat loss and our use of pesticides. Declines are widespread among many common and abundant species that play important roles in food webs, Marra adds.

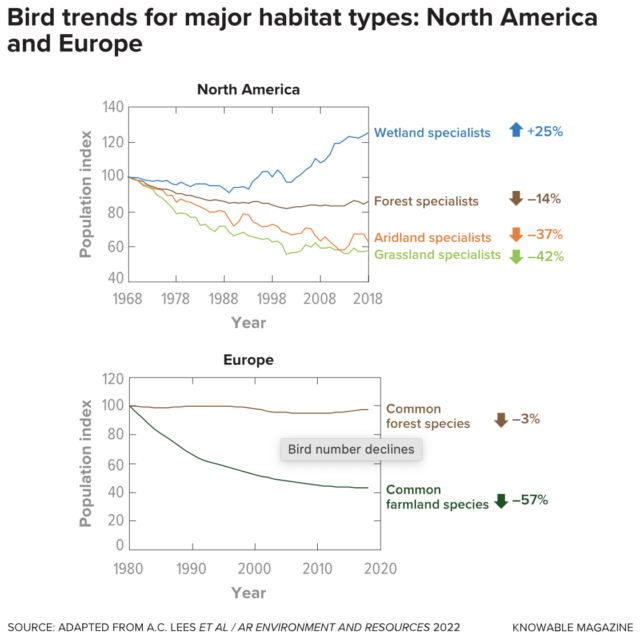

And it’s not just North America. In the European Union, a 2021 study of 378 species estimated that bird numbers fell by as much as 19 percentfrom 1980 to 2017. Data are scarcer on other continents, but reports are starting to chronicle concerns elsewhere, too. At least half of the birds that depend on South Africa’s forests have experienced shrinking ranges (with population trends yet to be assessed).

And in India, using citizen science data from eBird, a 2020 report estimated shrinking numbersin 80 percent of the 146 species examined—nearly half with declines of more than 50 percent. Overall, 13 percent of birds worldwide are threatened with extinction, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature’s red list a comprehensive source of information on the extinction risk of the world’s plant, animal, and fungus species.

Recently, Lees and colleagues pulled together all the data they could find on on the state of the world’s birds, publishing in the 2022 annual review of environment and resources It was an attempt to, for the first time, synthesize research from across the world to create a comprehensive picture of global changes in bird abundance. “Looking across all taxa, there are big signals for declines everywhere,” Lees says. “There are some species which are increasing, but more species are declining than are increasing. In our attempts to halt the loss of global bird biodiversity, we’re currently not succeeding.”

Silver linings

Even as they reveal a downward slide, bird surveys offer some hopeful signs. Wetland species in North America have grown by 13 percent since 1970, according to the 2019 Science study, led by a 56 percent rise in waterfowl numbers. The paper credits billions of dollars allocated to the protection and restoration of wetlands, often for the sake of hunting. In India, 14 percent of assessed bird species have been growing in abundance. Those successes, scientists say, show that it is possible to reverse population declines.

There are plenty of examples of birds that have been saved from extinction by people, adds Philip McGowan, a conservation scientist at Newcastle University in the UK. To assess the impacts of conservation actions, he and colleagues made a list of bird and mammal species that were listed as endangered or extinct in the wild on the IUCN Red List at any point since 1993.

For each species, they collected as much information as they could about population trends, pressures driving the species to extinction, and key decisions or actions taken to protect them. Over daylong Zoom calls, small groups of researchers hashed out the details before everyone assigned each species a score indicating how confident they were that conservation actions had influenced the species’ status.

For some birds, the researchers were able to definitively link conservation efforts with species survival. The Spix’s macaw, for example, has continued to exist only because it has been kept in captivity. And the California condor clearly benefited from the ban of lead ammunition, as well as captive breeding programs and reintroductions, among other measures.

But for other species, there was less certainty. The red-billed curassow of eastern Brazil, for one, faces threats of habitat fragmentation and hunting. Protected areas intended to safeguard it aren’t always well enforced, making it probable but less clear that conservation has helped the species.

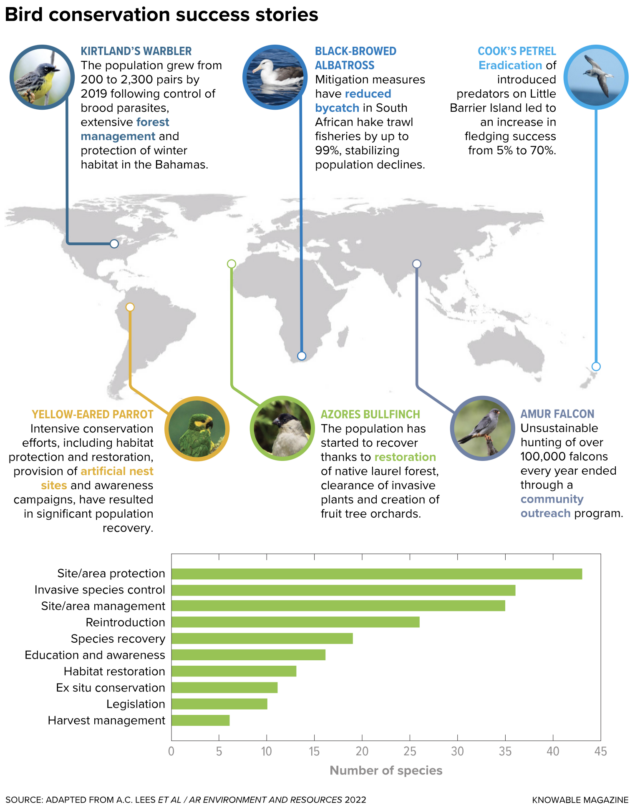

Overall, the researchers reported in 2020, as many as 48 species of birds and mammals were saved from extinction between 1993 and 2020 (McGowan says that is likely to be an underestimate). The number of extinctions, the calculations showed, would have been three or four times higher or more without human intervention.

Those findings should offer hope and motivation to help more species, McGowan says. “If we look at what has worked, we know that we can avoid extinctions,” he says. “We just need to scale that up.”

Forging ahead

In 2020, the year after Marra and colleagues reported a loss of nearly a third of North American birds, they partnered with several conservation groups to launch the road to larger platform. The project has identified 104 species of birds in the United States and Canada that need immediate help and, of those, 30 that are highly vulnerable to extinction because of extremely small population sizes or precipitous declines.

For each species, Marra says, it will be important to learn what’s behind their shrinking populations. Currently, he says, “We’re not approaching conservation from a species perspective. And people are nervous about doing that … they view it as being just too difficult. But I maintain that we can figure it out, just like we’ve done with … all the species that almost disappeared because of DDT. We have the power and the understanding with new science and with new quantitative skills to identify the causes of decline and to figure out how we can eliminate those.”

Policies need to acknowledge the interests of local communities, adds McGowan. That’s a key focus of a new international agreement hat was forged at the end of 2022, when representatives from 188 governments met in Montreal for the United Nations Biodiversity Conference (COP15) and adopted a set of measures to stop biodiversity loss, restore ecosystems and protect Indigenous rights.

Involving local people can benefit biodiversity while respecting communities, McGowan says. In South America, for example, the yellow-eared parrot nearly went extinct, in part because people decimated palm groves, which are prime nesting habitats for the birds, to use the fronds in Palm Sunday processions. Successful conservation actions have included a community outreach campaign that encouraged people to stop cutting down wax palms and cease hunting the parrots. In 2003, the head of Colombia’s Catholic church halted a 200-year-old Palm Sunday tradition involving wax palms, and parrot numbers have since increased. “Working with local people meant that threat could be reduced,” McGowan says. Conservation, he says, should target the species that need action most urgently while ensuring that local people are not disenfranchised.

Better population estimates would help to inform conservation efforts, says Corey Callaghan, a global ecologist at the University of Florida in Davie. As it stands, wide margins of error are a problem, in part because estimating abundance is challenging and the sampling data are full of biases. Large birds are overrepresented in some types of citizen science data, Callaghan found in a 2021 study. And since contributors to the North American Breeding Bird Survey stand on the sides of roads in the daytime, Marra says, they miss nocturnal birds, marshland birds and birds that live in untouched landscapes.

Understanding and accounting for these biases could lead to better estimates, says Callaghan. In one example of how far off counts can be, total estimates of shorebirds called Asian dowitchers ranged from 14,000 to 23,000—until a survey in 2019 tallied more than 22 thousand of the birds on a single wetland in eastern China. Researchers can’t assess changes if they don’t have accurate baseline estimates, says Callaghan. To that end, he argues for more open sharing of databases and more integration of observations collected by researchers and citizen scientists. “If we want to preserve what we have around us,” he says, “we need to understand how much there is and how much we’re losing.”

As more data emerge, researchers urge optimism. “It’s really important not to have a doomsayer sort of position,” Lees says. Conservation has saved very rare species from extinction, he notes, and reversed declines in once-common species.